The Story of

the First Hindu Temple in the West

written by Swami Tattwamayananda

Temples in India have a long history. Building a temple in the Hindu tradition was considered to be a spiritually meritorious act that brought spiritual merit to the builder  and sanctity to the place. As a religious institution, temples have always played an important role in the history of religious practices in Hinduism, where traditionally a temple is conceived as a symbol or a combination of various symbols and, much like a human organism, is considered to be the abode of God, the immanent divine spirit. A temple is also a symbol of the omnipresent, cosmic, and transcendental dimension of God.

and sanctity to the place. As a religious institution, temples have always played an important role in the history of religious practices in Hinduism, where traditionally a temple is conceived as a symbol or a combination of various symbols and, much like a human organism, is considered to be the abode of God, the immanent divine spirit. A temple is also a symbol of the omnipresent, cosmic, and transcendental dimension of God.

The Brihat Samhita states that a temple is a microcosm of creation. Temples were conceived to be everlasting spiritual symbols of human effort and devotion (Yaavat chandraarkamedini—“as long as the moon, the sun, and the earth exist”). From the standpoint of the individual spiritual seeker, a temple represents the subtle body with the seven psychic centers mentioned in the Tantrik texts. A temple, in essence, is the link between man and God which helps us to evolve from the earthly level to the transcendental divine realm.

Swami Trigunatitananda’s universal Hindu Temple was built as a symbol (pratika) of the great Vedantic ideal that the ultimate reality is one and that every religion is an equally valid path leading to the same spiritual goal.

Texts like Aparajitaprichcha (a well-known text on traditional Hindu architecture) present the temple structure itself as the form of creation or as the physical body of God. Agni Purana, on the other hand, considers the sanctum sanctorum alone as the body of the presiding deity. All rituals performed in temples symbolize different stages in our spiritual journey to discover the presence of the immanent divine reality, or God, as residing in our own heart.

It is said that the history of God and religion is the evolution of the human consciousness of the divine, the history of our ideas and concepts of God. In the history of Hinduism, especially after the Vedic age, temples were centers of religious life. But conventional temple worship did not have anything to do with religious universalism as understood today. Credit should go to Swami Trigunatitananda for giving a universal dimension to the very concept of temple worship by building the Hindu Temple in San Francisco that has stood out as a picturesque landmark in the urban landscape of San Francisco.

Swami Trigunatitananda’s universal Hindu Temple was built as a symbol (pratika) of the great Vedantic ideal that the ultimate reality is one and that every religion is an equally valid path leading to the same spiritual goal. Every religion represents an expression of the same eternal, transcendental truth. This integral view of the ultimate reality and the diverse human attempts to reach that goal, as taught by Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda, formed the philosophical and spiritual symbolism of the Hindu Temple of San Francisco built by Swami Trigunatitananda.

A whole lifetime could have been spent in building a structure like this; but Swami Trigunatitananda seemed to be always in a hurry. Immediately after landing in San Francisco, he set himself to work. He had a clear idea about his mission. He reorganized the Vedanta Society and established it on a secure, traditional spiritual foundation. Every act of his remaining twelve years seemed to have spiritual significance, as evidenced, for instance, by the planning and building of the Hindu Temple in 1905.

Symbolism in Temple Worship

Symbols represent our efforts to understand the invisible and the abstract through the visible and the concrete. They help us to conceive of a higher and transcendental idea through concrete representations.

Symbolism plays a very important role in Hinduism, especially in the construction of temples and the rituals performed therein. Every act of worship and every form of the deity is raised to a higher level through philosophical and spiritual reinterpretation. The whole idea of temple worship is built on symbolism. Sound symbols, such as OM, the Gayatri-Mantra, Bija Mantras, and the sacred mantras chanted in various ceremonies, as well as the form symbols of different conceptions of deities, diagrammatic symbols like yantras, the Shiva- linga and the Salagrama, the lotus, the different elements and rituals of formal worship of various deities, especially in the temple installation ceremony, the upachaaras (five, ten, sixteen, sixty-four, or one hundred eight items, or articles, ceremonially offered with appropriate mantras to the deity invoked in the temple image), and the elaborate celebrations, like the Car Festival of Lord Jagannath of the Puri temple, all these have a deep symbolic significance.

A devotee experiences the fact that God, whom he worships in the temple, is, in reality, the divine spirit present in his own heart.

The symbolism of temples, as well as of all aspects of temple worship, are meant to help us to eventually realize the immanent presence of God in our own heart, because the light in the temple ultimately represents the light of our own soul, the atman. Thus, symbolism helps spiritual aspirants to transcend external rituals and ceremonies. A devotee experiences the fact that God, whom he worships in the temple, is, in reality, the divine spirit present in his own heart. Finally, this living presence of God then vividly manifests in one’s everyday life.

Symbolism in the Features of the Old Temple and Its Architecture

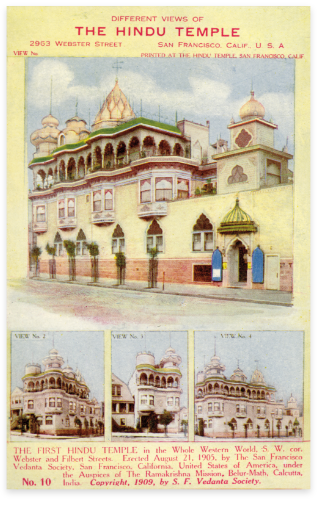

All the distinguishing features of the San Francisco Hindu Temple, or the Old Temple, as it is now referred to, are symbolic of a basic concept which Swami Trigunatitananda expressed in these words: “This Temple may be considered as a combination of a Hindu temple, a Christian church, a Mohammedan mosque, a Hindu Math or monastery, and an American residence.”

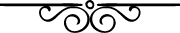

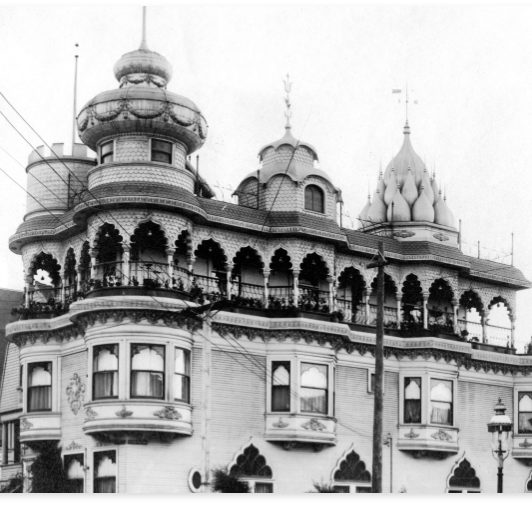

Left to Right: First tower (Benares temple replica); Second Tower (like one of the Shivamandirs of the Kali Temple, Dakshineswar); Third Tower (Shiva Mandir); Fourth Tower (castle tower of Europe)

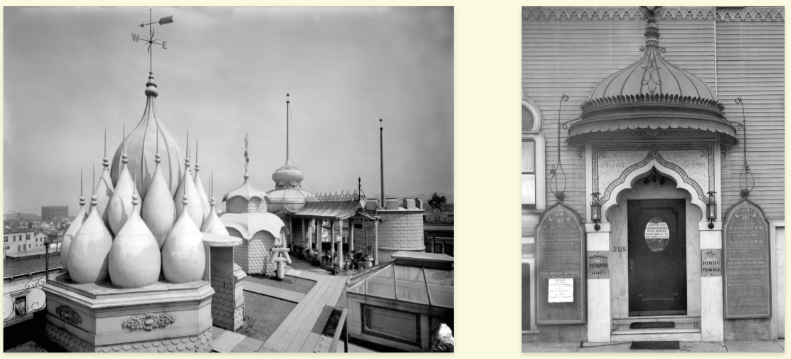

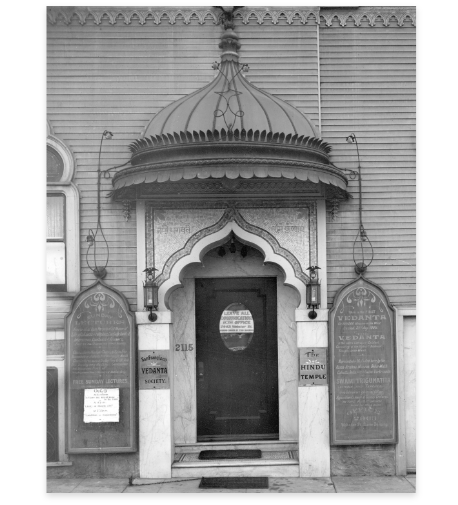

Hindu Temple Auditorium Entrance, circa 1910.

Left to Right: First tower (Benares temple replica); Second Tower (like one of the Shivamandirs of the Kali Temple, Dakshineswar); Third Tower (Shiva Mandir); Fourth Tower (castle tower of Europe)

Hindu Temple Auditorium Entrance, circa 1910.

The large round tower at the northeast corner of the building is fashioned after some of the modern provincial temples of Shiva of Bengal, complete with the usual emblems common to Shiva temples.

The next tower, west of it, is a model of one of the twelve small Shiva temples along the Ganges at Dakshineswar, near Kolkata, where Sri Ramakrishna lived and Swami Vivekananda and the other disciples of Sri Ramakrishna first came under his influence and training. This middle tower is surmounted by a combination of three symbols. First, it has a crescent form at the bottom, which is a Turkish or Mohammedan symbol, but this is also the type of symbol used by some Hindu devotional sects, as well, and represents the spiritual path of devotion to God. Second, the middle sign looks like the sun: Without sunlight and heat, we cannot grow, and, therefore, this symbol indicates the path of work or karma. The third symbol, in this group of three, is the trident, which in Hindu tradition is the scepter of Shiva, who destroys ignorance, and, therefore, it symbolizes the path of knowledge or of spiritual inquiry and philosophy.

The next tower, west of it, is a model of one of the twelve small Shiva temples along the Ganges at Dakshineswar, near Kolkata, where Sri Ramakrishna lived and Swami Vivekananda and the other disciples of Sri Ramakrishna first came under his influence and training. This middle tower is surmounted by a combination of three symbols. First, it has a crescent form at the bottom, which is a Turkish or Mohammedan symbol, but this is also the type of symbol used by some Hindu devotional sects, as well, and represents the spiritual path of devotion to God. Second, the middle sign looks like the sun: Without sunlight and heat, we cannot grow, and, therefore, this symbol indicates the path of work or karma. The third symbol, in this group of three, is the trident, which in Hindu tradition is the scepter of Shiva, who destroys ignorance, and, therefore, it symbolizes the path of knowledge or of spiritual inquiry and philosophy.

The particular order of these three symbols on one staff has additional meaning: Generally speaking, one must have a little faith and love to start some real kind of work. Therefore, the sign for the path of devotion has been put first. Then through love and faith comes a true sense of duty or work. Therefore, the path of karma has been put next. Then when we finish all our karma or work, and, when we become pure, we pierce through the veil of ignorance. Therefore, the sign of the path of knowledge has been put last. Another meaning can also be derived, as follows: Unless our spiritual culture transcends in greatness the sun, moon, and everything, we cannot reach the ultimate truth.

The next tower to the west, with its cluster of multiple small, pointed domes surrounding a large central dome, is a replica of one of the principal temples of Varanasi, the most ancient center of Hindu learning and spiritual tradition. This tower has also a little similarity with the top of the temple of Mother Kali at Dakshineshwar, as mentioned earlier. The small tower farther west, high above the entrance to the temple, is a miniature, modeled after the Taj Mahal at Agra in North India. On the southeast corner of the building is a crenelated round tower modeled after some of the old castle towers of Europe, which belong to the medieval era of Christianity. The veranda that runs along the third floor on the north and east sides of the building is lined with sculpted arches in Moorish style.

Over the entrance door to the temple is a canopy with further symbolism to illustrate the soul’s rise to spiritual insight and illumination. It also contains a mosaic inscription in Sanskrit which reads: Om Namo Bhagavate Ramakrishnaya, which means: “OM, salutation to the blessed Lord Ramakrishna”; OM being a word indicative of divinity in its most universal aspect, namo or namah refers to salutation. The word bhagavate or bhagavan, signifying Lord, implies that the holy personality, Sri Ramakrishna, named in this verse, is considered to have a divine, rather than a merely human origin and function.

The metal canopy above the entrance door is decorated around its edge with a fringe of lotus petals, symbolizing the inner mental lotuses of increasing beauty seen by mystics in meditation. The whole is surmounted, as though protected, by an American eagle with wings outspread. The eagle seems to fly beyond this world, which is the realm of creation, preservation, and destruction—the realm of relativities. The eagle can also be seen as expressive of the Hindu mythological bird, Garuda, the symbol of great strength, spiritual devotion, and of steady and rapid progress.1

Swami Trigunatitananda, while answering a question as to whether one had to believe in rebirth or in any such doctrine, in order to reach the highest spiritual goal, said: “There are many faiths and religious sects in the world, which do not believe in nor care to believe in such doctrines; according to Vedantism, they, too, reach the very highest; one should simply go on sincerely, ardently, and steadily along one’s own faith, with one’s own beliefs, with a view to advance to the very highest.”2

Swami Trigunatitananda wanted to construct a building in San Francisco that would be an architectural representation of the message of religious harmony, a medium for communicating the Vedantic universalism that was the central theme of Sri Ramakrishna’s message to the modern world, as so ably expounded by Swami Vivekananda. That partly explains his decision to build a temple so unlike the traditional Hindu temples in India, yet incorporating many of their aspects like the pointed towers, domes, etc. The message of the Old Temple was the message of religious harmony, based on the fact that spiritual experience knows no barriers of race, nationality, or external practices.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the whole work was the amazing speed of the construction of the temple—an astonishing feat accomplished within less than five months! Swami Trigunatitananda installed the cornerstone on August 21, 1905, and the dedication ceremony was held on January 7, 1906. This original structure had only the tower at the northeast corner of the building. That tower was removed in 1908, and an additional floor was added to the building. Along with all the other towers now seen, the corner tower was reinstalled.

The First Hindu Temple in the West, after 1908

One of Postcards printed at the Hindu Temple, 1909

These events were historically significant when we remember the cultural and spiritual landscape of America during this period. The country was undergoing a radical transformation in the field of religion and spirituality. New concepts and movements like Theosophy, Christian Science, and Unitarianism were becoming popular among the social elites in the United States. Higher Hinduism, or Vedanta, had just been introduced to American society by Swami Vivekananda in the World’s Parliament of Religions at Chicago in 1893 and subsequently through his lectures and classes. Its catholicity, rationality, and especially its open acceptance of other faith-systems were in sharp contrast to the narrow dogmatism of the contemporary Christian church. The intellectual challenges of Darwinist, humanist, and atheistic movements, as well as the criticism of the admirers of the latest scientific discoveries, posed a great threat to exclusivist claims of established religions.

In conclusion, the earliest temples of North and central India belonging to the Gupta period (320-650 A.D.), the rock-cut temples of South India belonging to the periods of the Pallavas, Chalukyas, and Rashtrakutas, as well as the temples of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, are marvels of ancient Hindu architecture, as are the temples belonging to the Vijayanagar period and the great ancient Indian temples that exist in places like Kashi, Vrindavan, and Mathura.

From an architectural point of view the San Francisco Hindu Temple is different from both the South Indian or Dravida and Chalukya temples with their characteristic tiered vimana shrines, their axial and peripheral mandapa adjuncts, and towering gopura entrances (gates), as well as from the North Indian temples with their own distinctive features like a square plan and curvilinear towers, representing the nagara style. Also, there is no evidence to show that Swami Trigunatitananda fully adhered to the principles of temple construction as laid down in the traditional texts on Vastu Shastra like the Brihat Samhita.

Swami Trigunatitananda, a great traditionalist, must have performed all the rituals before the temple construction, like sanctifying the earth, Vastu puja, garbha-nyasa, etc. But, since the Temple did not have a traditional inner sanctum sanctorum like the traditional orthodox Hindu temples in India, many of the rituals were perhaps not required.

A Spiritual Saga of Dedication and Service

Considering the circumstances under which he was deputed by Swami Vivekananda to take up the Vedanta work in San Francisco, Swami Trigunatitananda knew it was to be a heroic task. The reorganization of the Vedanta Society, keeping the congregation together, and carrying on the task of spreading the message of Vedanta in northern California—all these endeavors demanded exceptional organizational skills, spiritual insight, moral strength, ingenuity, drive, iron determination, and, above all, a blending of the dedicated action of a missionary and the profound spirituality of a saint. It was remarkable that, even in the midst of Swami Trigunatitananda’s active dynamism on display throughout his more than twelve years of spiritual ministration in San Francisco, there were always glimpses of his monastic humility and contemplative nature.

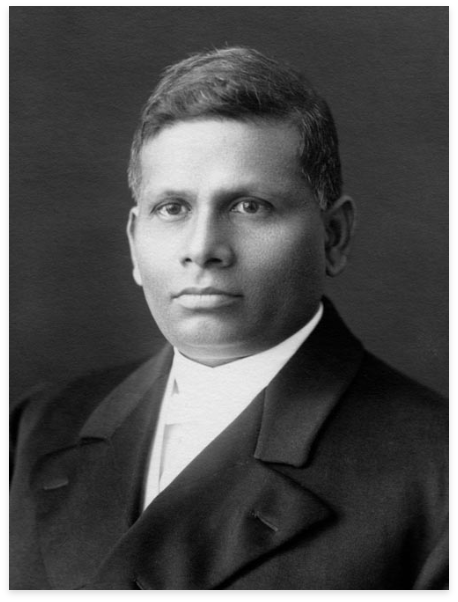

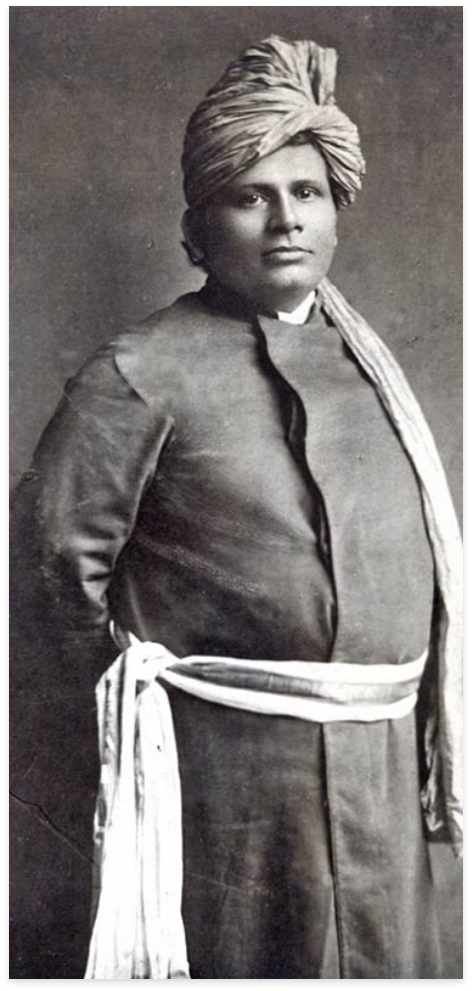

Swami Trigunatitananda

About this builder of the Hindu Temple, one may well say what William Arthur Ward stated about an ideal teacher: “The mediocre teacher tells. The good teacher explains. The superior teacher demonstrates. The great teacher inspires.” Swami Trigunatitananda’s sense of dedication was an inspiring example for all those who worked with him to build the Temple.

The universal Hindu Temple of San Francisco has a special significance in the present age which is characterized by a widespread urge for anything universal. Unity in variety is the theme for our times. This urge for universality, especially in the field of spirituality, is bound to prompt thinking people everywhere to study the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna and his ideal of universal religious harmony symbolized in the universal Hindu Temple of San Francisco.

Was the building of the Hindu Temple an accident? If Swami Turiyananda had not left San Francisco in 1902 and Swami Trigunatitananda had not arrived in 1903, probably it would never have been built. But, when we look back after more than a century, we can see that there was a divine hand and divine plan behind it. Swami Trigunatitananda experienced this as a fact, as he revealed from time to time. On one such occasion, he said, regarding this first Hindu Temple in the West: “I shall not live to enjoy, others will come later who will enjoy.” With reference to his own motivation, he boldly stated: “Believe me, believe me, if there is the least tinge of selfishness in building the temple, it will fall, but if it is the Master’s work, it will stand.” 3 And it has stood, weathering more than a century, including the catastrophic 1906 earthquake and the fire ignited by it, which was fanned by unrelenting winds to within six blocks of the Temple, before suddenly being diverted by a providential reversal of wind direction.

The story of the universal Hindu Temple of San Francisco is not just the story of a temple. It is the saga of a saint—a humbling, inspiring model for all spiritual seekers.

San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge

Old Temple, Sri Ramakrishna’s birthday, 1952

This commemorative volume is a humble tribute to Swami Trigunatitananda and his work: the universal Hindu Temple of San Francisco. He spent the last twelve years of his life spreading Vedanta in San Francisco and in the Bay Area and, quite literally, died in its cause. This volume contains photos, newspaper reports, articles, and several other items related to the universal Hindu Temple in its one hundred ten year history. It also takes the reader on a spiritual journey that explores several little-known aspects of a heroic spiritual saga that unfolded during the early decades of the 20th century.

The First Universal Hindu Temple in the West Read More

Swami Trigunatita and the Symbolism of the Old Temple

Swami Trigunatita, a direct disciple of Sri Ramakrishna, succeeded Swami Turiyananda in 1903 as minister of the Vedanta Society of San Francisco as it was known in its early years. He was in charge for twelve years, during which time he laid a firm foundation for the Society’s future growth and development. Swami Trigunatita was a unique personality, energetic and imaginative. He had deep love and loyalty to his brother monks, Swami Vivekananda and Swami Turiyananda, though his method of work was diametrically opposite from theirs. He, like them, dedicated his entire life to the Vedanta movement either in India or in the West, throwing himself completely into the work until the end of his life. The swami had remarkable stamina coupled with tremendous will power. Further, one of his outstanding characteristics was his organizational ability. All of these qualities combined resulted in the magnificent temple, originally entitled the Hindu Temple. The building of the Old Temple was a remarkable feat for a variety of reasons—the most amazing being the speed with which the temple was built. The work began in August 1905 and the temple was ready for dedication in January 1906. Within four months the swami had accomplished an almost unimaginable task. Initially the temple had only two floors.

Swami Trigunatita

The third floor and four main towers were added two years later. The other unusual aspect of the temple is that Swami Trigunatita himself designed it, blending elements of Eastern and Western culture, both religious and secular. The architect, Joseph A. Leonard, who based his blueprint on the swami’s ideas, mentioned that he learned more about the construction of the temple from the swami than the swami did from him. Swami Trigunatita’s conceptual design is expressed in both the architecture and symbolism that is embodied in the structure.

The swami was always intent on synthesizing the best of the East with that of the West, just as his illustrious brother Swami Vivekananda had done. Sister Gargi wrote, “To Swami Trigunatita the first Hindu Temple in the whole Western world would be a vital piece of India planted on American soil. The Temple represented the influx of India’s great spiritual wisdom into the culture of the West—there to grow and flourish, as Swami Vivekananda had wanted.”

In a pamphlet that he published, “General Features of the Hindu Temple,” he explained the style and the symbols, stating, “This Temple may be considered as a combination of a Hindu Temple, a Christian church, a Mahommedan mosque, a Hindu math or monastery, and an American residence.”

After the third floor was added, the temple was rededicated in 1908. A San Francisco newspaper article described the extraordinary architecture of the Hindu Temple. Excerpts from the article state: “The temple itself is one of the most striking meeting places… in San Francisco. While covering but a comparatively small area, its cluster of gourd-like domes, its tower of meditation, and its minarets invest it with the appearance of having been transplanted from sacred Benares. The architecture of the roof is a composite of detail from the Taj Mahal at Agra, the Temple of Shiva at Bengal, and of the Temple Garden of Dakshineswar at Calcutta, where Paramahamsa Sri Ramakrishna, the great master of Swami Vivekananda, and other adepts once lived.

“A canopy over the mosaic and marble entrance to the auditorium is made to represent the thousand-petaled lotus in the brain, which, when opened through concentration and meditation, the Vedantists believe, brings the highest spiritual illumination. A Sanskrit inscription on the mosaic arch of the auditorium entrance reads, Om Namo Bhagavate Ramakrishnaya. Om is the symbolic word for the absolute and is frequently chanted or repeated in spiritual meditation. Namo means salutation, and Bhagavate Ramakrishnaya means to the blessed Lord, Ramakrishna.”

Mention should be made of another tower over the entrance to the auditorium which resembles a bell-tower of a Christian church, somewhat a Mahommedan mosque, as well as a partial miniature of the Taj Mahal of Agra. The tower was used as a conservatory, which symbolized all living things. The swami even included the American eagle in his design above the door, comparing this famous American icon with the mythical bird, Garuda, of ancient India.

The swami had a cordial relationship with whomsoever he came into contact. He felt strongly that he should integrate with Western culture and society. Accordingly he met all kinds of people in San Francisco—city officials, fireman, tradesman, street car conductors, shopkeepers, etc.—all were charmed by him. In 1912 he sought permission to plant trees around the temple, which required taking two feet of the existing public sidewalk. He contended that a garden of shrubs and other plants would enhance the attractiveness of the building, which in turn would reflect well on the city, especially during the Panama Pacific Exposition that was to be held in San Francisco in 1915. The mayor and board of supervisors granted him the necessary permit. He also succeeded in getting a tax exemption for the temple, as well as the right to sell Vedantic books without the usual license fees necessary for sales.

Swami Trigunatita’s vision for the growth and spread of Vedanta in the West was unique. He conceived of Vedanta as an organic unity, which included every religion, the East and the West, and all philosophical thought. The Old Temple, which survived the great 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, is a living testament to the great swami’s universality and dynamism.

For more details see Swami Trigunatita: His Life and Work

- Sister Gargi (Marie Louise Burke), Swami Trigunatita: His Life and Work (San Francisco: Vedanta Society of Northern California, 1997), 198-203.

- Ibid., 373.

- His Western Disciples, “The Work of Swami Trigunatita in the West,” Prabuddha Bharata, March 1928:132.

Streaming

Streaming