The Beginning

During his first visit to the West, Swami Vivekananda (Swamiji) had often spoken of the need in America for a Vedantic ashrama or retreat. But it was not until early in 1899, when a student of Swami Abhedananda’s renounced  the world and received the brahmacharya name of Gurudas, that the need became real. When it was discussed in the New York Society, of which Swami Abhedananda was in charge, another of his students, Miss Minnie C. Boock, offered a solution.

the world and received the brahmacharya name of Gurudas, that the need became real. When it was discussed in the New York Society, of which Swami Abhedananda was in charge, another of his students, Miss Minnie C. Boock, offered a solution.

She possessed, it so happened, a homestead in Santa Clara County, California, that had been issued to her some eight years earlier by President Harrison, and that contained, according to the Official Plat of the Survey, “one hundred and fifty-nine acres and eighty-nine hundredths of an acre.”

This property could, she thought, serve the purpose of an ashrama. “It had its disadvantages,” Swami Atulananda (formerly Cornelius J. Heijblom, then Gurudas), later wrote; “it was fifty miles from the nearest railway station and market, but it would do to begin with. It would be solitary anyhow. And she very generously offered this place to Swami Vivekananda.”

On June 25, 1900, when Swamiji was in New York, Miss Minnie Boock formally deeded her homestead to him, “to have and to hold,” the record reads . . . “in trust, for the general use and benefit of the Vedanta School of Philosophy.” Thus the first Vedanta retreat in the Western world officially came into being.

In June 1900, Swamiji wrote that “It (Shanti Ashrama) would be nice for a summer gathering for us in California, if friends like to go there now I will send them the written authority. Will you write to Mrs. Espinol [Aspinall] and Miss Bell, etc. about it. I am rather desirous it should be occupied this summer as soon as possible. There is only a log cabin on the land, for the rest they must have tents. I am sorry I can not spare a Swami yet.”

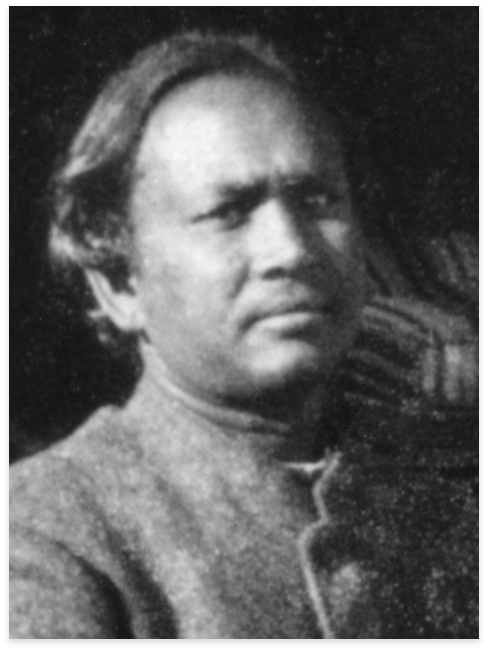

Swami Atulananda

Swami Turiyananda, 1901

In the meanwhile Swamiji asked Swami Turiyananda, to whom he had already assigned the California work, to establish the ashrama. “It is the will of the Divine Mother that you should take charge of the work there,” Swamiji told him. Swami Turiyananda smiled, “Mother’s will? Rather say it is your will. Certainly you have not heard the Mother communicate Her will to you in this matter.” But Swamiji grew grave. “Yes, brother,” he said, “If your nerves become very fine, then you will be able to hear Mother’s words directly.” He spoke with such fervor that Swami Turiyananda’s doubts were stilled. Even as a year or so earlier he had agreed, out of love for Swamiji, to come to America, so he now agreed to try to establish a retreat in far-off California.

Swami Turiyananda and Miss Boock traveled in Swami Vivekananda’s company as far as Detroit, where they evidently stopped over for a day or two. It was there, it seems, that Swami Turiyananda received directions from Swamiji regarding the future work. Speaking of these later, the swami enumerated them: “(1) Forget India; (2) go to the land; (3) establish the center; (4) Mother will do the rest.” Thus instructed, Swami Turiyananda, accompanied by Miss Boock, proceeded on to southern California where he arrived on Sunday, July 8.

Swami Turiyananda arrived in San Francisco on Thursday, July 26, and that evening was greeted by the Vedanta Society, which met as usual at Dr. Logan’s office. The discussion revolved around whether the swami would accomplish “most good by going away to the mountains with a few who would be able to go with him or by remaining in the city and shedding the influence of his life and teaching among the many he would be able to reach.” Swami Turiyananda’s reply was that he would do both; “that his work was with the few and the many.” But now he felt that he should go to the mountains, as the land had been given and “Mother” was propitious, and that after starting the ashrama he would return to teach in San Francisco and also go to Los Angeles. “I am your servant,” he said: “I have come all the way from India to serve you, and I will do my best.”

On the afternoon of Thursday, August 2, just a week after his arrival in San Francisco, Swami Turiyananda and eight students set out for the ashrama. These pioneers were Emily Aspinall, Ida Ansell, Dr. Milburn H. Logan, George Roorbach, Mrs. Bertha Petersen, Dr. Lucy A. Chandler, Mrs. Agnes Stanley, and one Mrs. Jackson. The first four had been well known to Swami Vivekananda. Four days earlier, Lydia Bell and Minnie Boock had gone on ahead to get things ready for the arrival of the group.

Minnie Boock, 1900

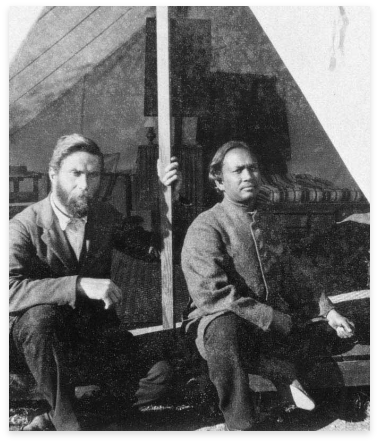

Swami Turiyananda and George Roorbach, 1901

Swami Turiyananda and the eight students, carrying luggage, provisions, tents, and other bulky equipment of diverse kinds, traveled by train to San Jose, a town some sixty miles south of San Francisco. They stayed overnight at a small hotel (the Rita) and the next morning at daybreak set out by horse-drawn stagecoach for Mount Hamilton, some twenty miles southeast. This second step of the journey was the most pleasant. The road, a fairly good and well-traveled one, wandered through fragrant, fruit orchards, through vineyards and olive groves, past well-kept farms and dairies, and, at length, wound — twisting three hundred and sixty-five times in five miles — up Mount Hamilton to Lick Observatory, from which summit of 4,200 feet one could see on a clear day for a hundred miles in all directions.

But just here, at the peak of the journey, the aspect of things alarmingly changed. Waiting for the party of nine was a Mr. Paul Gerber, a young Italian-Swiss homesteader, whom Miss Boock had sent. He had brought the only available conveyance in the valley—a small, four-seater spring wagon, drawn by four mules, which could accommodate seven people, including himself: four on the seats, three on the floor with legs dangling, country-style, over the back. But with space thus filled there was no room for the luggage, the provisions, the tents, and the equipment—all of which, Mr. Gerber explained, would have to be left at the mountaintop. Further, his mules could make only one trip every other day up the steep, difficult road; thus it would be some time before the baggage could be recovered.

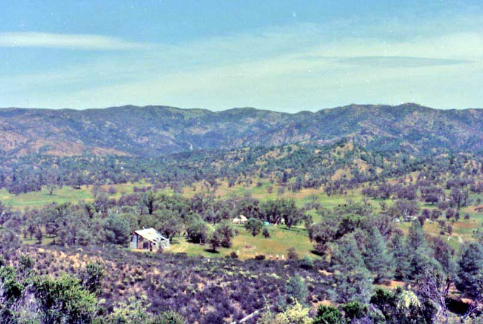

As for the three remaining people, two horses were borrowed from the Observatory, one for Mrs. Stanley, the other for Dr. Logan. Mr. Roorbach, who had brought along a bicycle, had perforce to ride it. Disheartening as this turn of events was, a look to the east of Mount Hamilton was more so. Here were no orchards, no vineyards, no well-irrigated fields, no shaded farmhouses, or well-kept barns. A rugged confusion of mountains, partly covered with chaparral —a scratchy small-leafed scrub — and dotted with oak and scraggly digger pine, shimmered in the heat. Nowhere was there sign of human life.

At the base of the farthest range stretched what appeared to be a long, narrow strip of brownish grass. This, as Mr. Gerber could have pointed out, was the San Antonio Valley, somewhere in which lay Miss Boock’s homestead. The valley upon which Swami Turiyananda must have gazed from the top of Mount Hamilton was not — nor is it today — to be found on an ordinary map; few Californians could have said where it was, what it was, or how to get there. “Mother,” Swami Turiyananda murmured, “where have You brought us? What have You done!”

The road that twisted some fifteen miles down, around, up, and over the mountains and into the valley has been described in her memoirs by Mrs. French, who traveled it several years later, as “almost impassable — rocks, fallen trees, in some places almost washed away. Only a cowboy on horseback could traverse it with safety.” Indeed, for long distances this road was no road at all but a long-dry, gravelly creek bed, overgrown here and there with brush. As the afternoon wore on, the heat became oppressive, and at length Mrs. Stanley fainted dead away and tumbled from her horse. Though unhurt, she was shaken, and the swami insisted upon giving her his place in the wagon beside the driver. He himself now rode the horse.

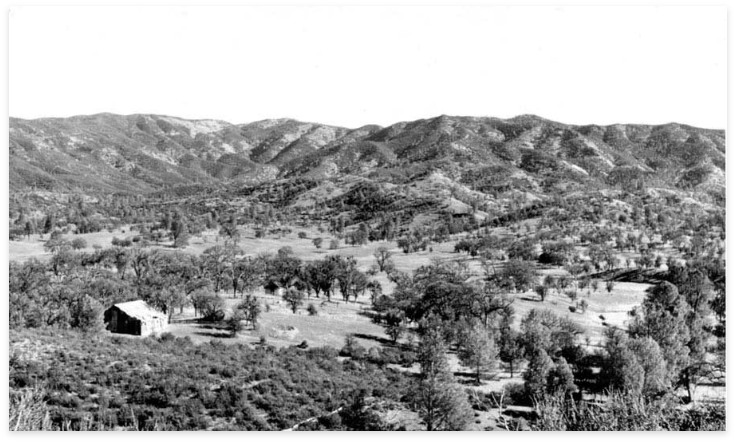

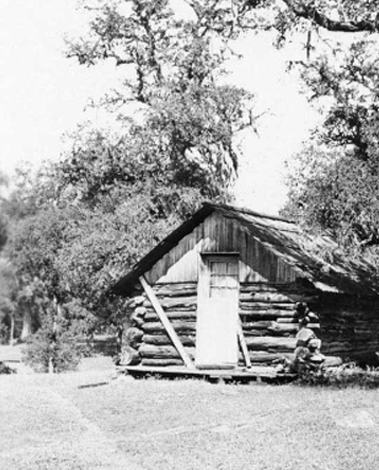

Shanti Ashrama, view from southwest

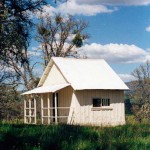

Log Cabin

It was seven o’clock, the sun had set behind the western range, and the mountains in the east were a deep and lovely mauve when the party arrived at the ashrama at the south end of the valley. There they found a small (twelve-by-twelve-foot) log cabin, a shed, a tent, and Miss Boock and Miss Bell.

These women had been having trouble of their own. During her absence much of Miss Boock’s furniture and equipment, such as cots, camp stools, lamps, and utensils, had been appropriated by other homesteaders whose cabins, now deserted, were located long distances one from another. Miss Boock, accompanied by Miss Bell and Mr. Gerber, had driven about the sweltering valley in the spring wagon, discovering and repossessing some, if not all, of her property.

These foraging trips, together with cleaning out the long-unused cabin and shed, re-equipping them, putting things in order, must have been arduous tasks. But on the evening of August third all was in readiness, and the rudiments of dinner — boiled rice and brown sugar — were waiting for the swami and his party. The rest of the meal, which was to have come with the group and been cooked upon arrival, was sitting atop Mount Hamilton. Thus Shanti Ashrama became established.

Swami Turiyananda

From the moment Swami Turiyananda gazed gravely upon San Antonio Valley envisioning the task before him, to the day he left the ashrama for good, he spent his entire time trying to fulfill what Swami Vivekananda had commissioned him to do — to create a retreat where spiritual seekers could practice intensely. Swami Turiyananda was a jivanmukta, which according to Vedanta is defined as one who is freed while living, having transcended body consciousness, and is immersed in the divine Reality. The swami, steeped in the Vedantic scriptures, had been drawn from a young age to study and meditation. He had memorized a phenomenal number of Vedantic and other religious texts and teachings. But more than being a profound scholar, he had assimilated what he studied and verified it through his own direct experience.

The swami was not only learned in the scriptures, but was also a perfected yogi; he had extraordinary control over his mind, which always remained in a state far beyond the realm of nature. Sister Gargi observed, “The residence of a great soul can create a great retreat, and this, one thinks, is why Swami Vivekananda asked so very great a soul as Swami Turiyananda to establish a center there.”

Swami Turiyananda at the Shanti Ashrama gate, 1900

Such was Swami Turiyananda, a man of God so pure that his mere presence in the ashrama continues to sanctify the grounds to this day. The swami spent long hours there meditating, chanting, studying—communing with the Divine. He set in motion an exceedingly subtle force that when one enters the ashrama something within resonates in response. He himself gave the property the apt name Shanti Ashrama. When Frank Rhodehamel asked the swami why he felt it was an ideal place, the swami replied, “It is an ideal place for an ashrama.” Rhodehamel continued, “What do you mean by ideal for an ashrama?” “It is a good place to meditate on God,” he answered, giving a little characteristic backward tilt to his head and looking at me with an amused expression in his half-closed eyes.”

Various firsthand recollections of Swami Turiyananda provide a vivid picture of the swami as he moved among the students teaching, sometimes formally, more often informally, encouraging, scolding, correcting faults, breaking obstructive habits, but always lovingly supporting them, molding their lives and characters.

Gurudas recalled: “To live with the swami was a constant joy and inspiration and it was an education, for one was learning all the time. And we all felt that spiritual help came through him. Sometimes gentle, sometimes the “roaring lion of Vedanta,” the swami was always fully awake. There was not a dull moment in the ashrama.”

The swami was an ideal leader of a contemplative retreat in such a solitary place with the closest neighbors twelve miles away. Though there were many practical issues and problems from scarcity of water to extremes of temperature — searing heat in summer and freezing cold in winter — he nevertheless kept the minds of his students pitched high, always exhorting them to let go of smallness and to remember Mother: “Think of Mother; forget worldly things. Here it must be only Mother — no city here. Forget everything and think of Her.”

Under his direction the meditation cabin was constructed by George Roorbach, who also built three other cabins and a kitchen cellar. Getting materials for building was a task of great difficulty, as the way there was through pioneer country, with wagon trails for roads, and the nearest source of supply was San Jose, forty miles away over the mountains. But their heart was in the work and they persevered until they had erected a kitchen and screened dining room, a log cabin, several outhouses, three canvas-walled cabins and a small meditation cabin, which stands to this day. One of the springs on the ground was deepened, rock-lined with cement and the water carried in empty kerosene cans to the cabins as needed. Everyone, including the swami, participated in the work: chopping wood, carrying water from the well, cooking, cleaning, clearing brush, working on the new buildings, etc. Referring to Swami Turiyananda, Mr. Allan wrote in his history: “He would ask someone to go with him, say, to get water, and on the way he would feed the soul just the food that could be taken at that time; again, he would come into the kitchen while a meal was being prepared, and any small incident would call forth a lesson or story to make clear some question which was in the mind of someone there.”

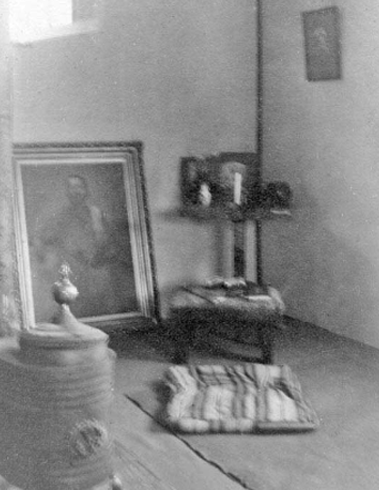

Swami Turiyananda’s cabin, 1901

Meditation Cabin interior

The evening campfire was inaugurated almost upon arrival, continuing nightly thereafter. Ida Ansell, who had been with Swami Vivekananda at Camp Taylor and was among those in the original group with Swami Turiyananda, remembered the first campfire at the ashrama: “We sat in a circle around the fire and listened to swami’s deep, rich voice chanting in melodious Sanskrit, ‘We meditate on the adorable and effulgent light of Him who has produced this universe. May He enlighten our hearts.’ We felt only a sublime tranquility. . . . It seemed as though the past with all its hours of tragedy and moments of foolish joy had been blotted out — a sort of vague dream — and real life began at this moment.”

Those fortunate retreatants were invigorated in his presence and were swept into the current of his spirituality. “The swami,” Gurudas wrote, “never spared himself; he did not think of his own health or comforts; he had only one object, namely to bring those eager students to the feet of his Divine Mother . . . the swami’s ardor was infectious.” It was his custom to awaken everyone at dawn by gently wending his way between the tents and cabins softly chanting all the while. In fact, it has come down to us that he chanted from morning until far into the night at times. The tenor of his chant would vary; while the students were working it would be in a major key, vigorous and strengthening; everyone felt energetic and full of enthusiasm, and the work was done joyously.

Life at the ashrama required tremendous effort. He encouraged self-discipline; he wanted the students to excel in an atmosphere of freedom. But he was ever watchful, cautioning Ida Ansell, he said, “What you want you will get. Be sure of it. If you want entertainment, you will get entertainment. If you want Mother, you will get Mother. So be careful.”

In the meditation cabin, a Chinese table served as an altar on which was placed a photo of Sri Ramakrishna and Swamiji, incense, and a vase of flowers. The disciples sat on pillows or low boxes against the walls, while swami sat under the window opposite the door. He would enter the cabin last after everyone had been seated. Before he began chanting, he would glance around the room, as if he were gathering the reins of restive horses to bring them under control. Then it was reported he began chanting “softly in a minor key and would continue until all restlessness had subsided.” Someone asked once what the chanting meant, and the swami replied: “It is lashing the waves of the mind into submission.” As he continued to chant, the minds of those present would settle down, becoming quiet and peaceful. An hour later when the swami’s chant would begin again “it seemed to us,” one of those present recalled, “to come from a long distance.” The students were often disturbed during their meditation by flies, mosquitoes, and other insects, but never the swami, who remained perfectly oblivious of all external circumstances, seated perfectly still totally absorbed within himself.

Although meditative by nature, the swami was equally approachable and full of fun and concern for all. When someone suggested making rules, he replied: “Why do you want rules? Is not everything going on nicely and orderly without formal rules? Don’t you see how punctual everyone is, how regular we all are? No one is absent from the classes or meditations. Mother has made her own rules, let us be satisfied with that. Why should we make rules of our own? Let there be freedom but no license. That is Mother’s way of ruling.”

Once when someone remarked that it was amazing that people with such diverse temperaments could live together peacefully. The swami responded: “You are all tied to me by the string of love. How else would it be possible? Don’t you see how I trust everyone and I leave everyone free? That I can do because I know that you all love me. . . . But remember, it is all Mother’s doing.”

Horse at Shanti Ashrama

Swami Turiyananda with walking stick

The swami was always particular about how work was performed. He himself was a meticulous worker, paying as much attention to the details as to the end result. To a student who had been inattentive to a task he had given her, he implored, “Make every act a worship. Whatever you do, do as an offering to Mother and do it as perfectly as you can.” He said repeatedly, “Don’t consider your work as mere secular work, rather regard it as worshipping the Lord. . . ‘Yoga is skill in action.’ Ordinary work, done in a spirit of dedication to the Lord and thus transformed into worship, becomes yoga. Such performance is a great feat! That work really becomes worship when it is done by effacing one’s ego and resigning oneself to God.”

The ashrama had a horse that drew the carriage, the only conveyance they had. The mare was allowed to roam freely in the fields. One day she gave them a merry chase, and after considerable effort, one of the men managed to toss a rope around her neck. Seeing the swami approaching, the man called out, “Swami, this mare wants liberation. But we have put a rope around her neck. Now she is caught in maya.” The swami laughingly replied: “Yes, we have bound the mare in maya. Yet we want liberation from maya ourselves. Be careful! Let not the fate of the mare overtake you. Cut the bonds of maya and be free.”

The swami often went for walks with the students. One day they climbed a steep hill, from which they had a stunning view of the valley. Seated under a pine tree, in almost tangible silence, with only a slight breeze blowing, the swami told those with him that the Divine Mother wears a heavy veil and that none can lift it except Her children. “What is Mother and where is She?” someone asked. “She is everything and everywhere. She permeates nature; She is nature. But talk won’t do. You must lift the veil.” “How, swami?” “Through meditation,” he replied. Always, he stressed meditation. “Meditation is the key that opens the door to Truth. Meditate, meditate, meditate until light flashes into your mind and the Atman stands self-revealed. Not by talk, not by study, but by meditation alone the Truth is known.”

Early in September 1901, exhausted, ill, and badly in need of rest, Swami Turiyananda left Shanti Ashrama. He returned in early January 1902, although still ill. Receiving news of his brother’s illness, Swami Vivekananda became increasingly concerned and in March 1902 he wrote to the President of the Society, Dr. Logan, asking that the swami be sent back to India. Swami Turiyananda returned to India in June 1902.

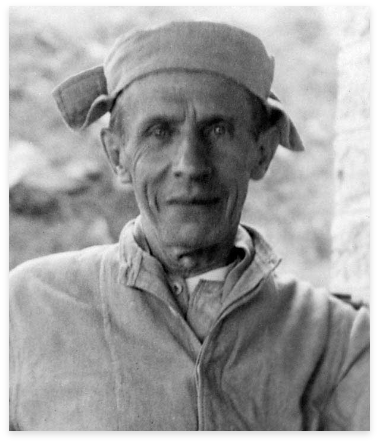

Gurudas

In December 1900, Gurudas arrived at the ashrama from New York and to Swami Turiyananda’s joy stayed on. A brahmachari, having taken his first vows, and a most mature spiritual aspirant, he helped Swami Turiyananda in untold ways; Eloise Roorbach said the swami often spoke gratefully of his help. It is primarily through his reminiscences that we learn the nature of the swami’s teachings at the ashrama.

Cornelius Heijblom (Gurudas), 1900

“Then he began to chant Om, Om, Om, his body rocking to and fro with the rhythm of the chant. After a few moments he suddenly stopped, and straightening himself said with great force, ‘Control your passions—anger, jealousy, pride. And never speak ill of others behind their backs. Let everything be open and free. When anything has to be done, always be the first to do it. Others will follow. But unless you do first, no one will do. You know how I have done all kinds of physical work here, only for that reason.’

“But what about the classes, swami? What shall I teach? I am a student myself.” ‘Don’t you know yet, my boy, that it is life that counts? Life creates life. Serve! Serve! Serve! That is the greatest teaching. Be humble! Be the servant of all! Only he who knows how to serve is fit to rule. But you have studied many years; teach what you know. As you give out, so you will receive.’

“Swami,” I ventured, “when you are gone we will be like sheep without a shepherd.” ‘But I will be with you in spirit,’ he said solemnly.”Gurudas was a most appropriate choice to carry on the work, since he was beloved by all for his gentleness of spirit and his steadfast devotion to truth, and he was in charge until the new swami, Swami Trigunatita, arrived in January 1903. By temperament Gurudas loved solitude. He lived an austere life at Shanti Ashrama for long periods of time in tune with nature, never caring for his own convenience or comfort. In spite of a bad back, he would bathe in cold water in freezing weather and work hard physically — chopping wood, carrying heavy buckets of water, and tending the garden. He was an earnest student of Vedanta, spending long hours in study and reflection, as well as writing a long commentary on the Bhagavad Gita while living at the ashrama.

Later in life, Gurudas related how he would be alone with no human being around for miles. Sometimes he would feel lonely, but when he entered the meditation cabin that feeling would vanish. “I was there altogether for five years. I meditated and studied much, and I worked too, he said. “Many times I would be alone there and I didn’t feel bored. Once as I was watering some plants, a rabbit came and began to lick the leaves to quench its thirst. Then I took some water in the palm of my hand and the rabbit licked the water. I felt the touch of its rough tongue on my palm. On another day, which was Christmas, I found a small lily blooming in the lawn. I felt so happy on seeing it greeting me, as it were, a gift from the Lord.”

After Swami Turiyananda left for India Gurudas stayed on for several years as caretaker of the ashrama, continuing some of the traditions of the first swami in charge into the time of the second one, Swami Trigunatita. For example, Swami Trigunatita came in November of 1903 with a group of ten students for a month-long retreat. Gurudas was there to greet them, having prepared the tents and cabins in perfect readiness, including places neatly contrived where they could arrange their belongings, as well as water for drinking and washing, and a hot and bountiful meal in the dining room. In the morning they were awakened by Gurudas moving from tent to tent chanting Om, as Swami Turiyananda had taught him to do.Gurudas remained into the next period of the ashrama’s history until he went to India in 1906. After a few years, he had to return to America to recoup his health. He had other stays at the ashrama sometime during 1913-14 and again during 1919-22. In 1922 he went to stay in India permanently and became a sannyasin of the Ramakrishna Order with the name Swami Atulananda. He lived there a long time, inspiring several generations of spiritual aspirants, and died in 1966 at the age of ninety-six.

Gurudas with Horse

Gurudas and Frank Rhodehamel

Gurudas on cabin porch, 1920

Gurudas and Meditation Cabin

Swami Trigunatita

The second great period of Shanti Ashrama was Swami Trigunatita’s time. It lasted from 1903 until his death in 1915. Swami Trigunatita was also a brother disciple of Swami Vivekananda and was selected by Swamiji to succeed Swami Turiyananda in the California work. A prodigious worker and an imaginative thinker, Swami Trigunatita entered the project of Shanti Ashrama as he did everything else—joyously and vigorously. He at once recognized the important part Shanti Ashrama would play in the work. His first retreats were held in November. Later on, as more people came and wanted to join his classes, he held them in June. Practically every year until his death, swami and his students would travel by train to Livermore, stay overnight in a hotel and spend the next day traveling through the valley to Shanti Ashrama.

Swami Trigunatita, 1903

His method was to hold month-long retreats in the study and practice of Vedanta for usually some forty students. His orderly mind had long recognized that in large classes organized for the study of yoga practices, the average students would progress more rapidly and the work of the class be advanced by regularity of activities and a certain amount of discipline. He called his retreats Yoga Classes, and this included all the four yogas. He also provided plenty of time for relaxation.The retreatants built sturdy permanent buildings, including a large dining hall and kitchen to accommodate fifty people, cabins for the swami and for themselves, a large barn for cows, horses, and farm equipment, a windmill with an elaborate water system, and platforms for outdoor meditation and scripture classes. These platforms were large enough to seat fifty people under a large spreading oak tree called the Meditation Oak or the Om Tree—because the symbol Om was painted on its trunk. The swami sat on the raised platform near the trunk and led the group meditations and classes.

Some of the retreatants also came at other times of the year to improve the ashrama. They hauled their building materials by horsedrawn wagons over the rocky, winding road from Livermore, or they used the materials at hand, such as forked branches of trees to make an aqueduct. All this work was done with the same vigor, imagination, and enthusiasm that their leader, Swami Trigunatita, had. Even the swami himself would do such work. For example, he carved out a path up Dhuni Hill through chaparral by himself. He was also responsible for instituting many inspiring customs at the ashrama such as sitting all night performing spiritual practices, most especially meditation, before a fire at the top of Dhuni Hill, which was called the dhuni fire ceremony.

Yoga class, 1910

Swami Trigunatita at Om tree, 1910

Water system excavation, 1910

Mr. Gerber and his family learned to love Swami Trigunatita as they had Swami Turiyananda, and they also made many friends among the students. Also, the workers in the different departments at the Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton were also very fond of Swami Trigunatita and considered him their friend. He had the wonderful quality of being able to make the whole world his own and people responded most favorably.

At the ashrama every meal was a feast of spiritual instruction always beginning with the Sanskrit chant Om Brahmarpanam and closing with other Sanskrit chants, for, as Swami Trigunatita said, eating should be done spiritually and mentally as well as physically, and for that reason he always regarded it as one of the most important functions of spiritual life. From 1911 on Swami Triguanatita did all the cooking, assisted by some of the men in the preparation of the vegetables and setting the table. The women washed the dishes and kept the dining room and kitchen spotlessly clean.

His labors were incessant, often lasting far into the night. Sometimes the light in his window could be seen burning all night long. He was always the ideal monk; despising ease and luxury for himself, he set a constant example that inspired every disciple to follow to the best of their ability.

Adobe cabin, 1910

Dhuni Hill, 1910

Swami Trigunatita on the porch of his cabin, 1910

En route to Shanti Ashrama

Swami Prakashananda

The third period, Swami Prakashananda’s time, 1915 to 1927, was very much an extension of Swami Trigunatita’s time. Swami Prakashananda, a disciple of Swami Vivekananda, came from India in 1906 to assist Swami Trigunatita in the California work, and like Gurudas, he gave continuity to the ashrama work. As assistant swami, he helped build up the ashrama traditions, such as the singing and chanting programs, the dhuni fire ceremony, the Sanskrit classes, the daily karma yoga work periods and meditations, etc.

Swami Prakashananda, 1920

He continued these traditions during his period of leadership and also added a few touches of his own, such as the reading of an unpublished translation of The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna,the addition of a large photo of Holy Mother, Sri Sarada Devi, to the meditation cabin, and now and then providing a feast for the neighbors.

Since the automobile had entered into American life by then, it made travel to Shanti Ashrama somewhat easier, as one could make the journey from San Francisco in half a day rather than in two days as before.

The reports of Swami Prakashananda’s retreats were every bit as enthusiastic as those of the first two periods. Swami Prakashananda’s death in 1927 ended the regular retreats at the ashrama

Swami Prakashananda en route

Swami Prakashananda and group, 1920

Swami Prakashananda, 1920

Swami Prakashananda with neighbors, 1920

From 1927 Onward

The next period, which lasted until 1952, might be called the caretaker period, since the Vedanta Society maintained a caretaker, Mr. Arthur Bryan, to look after the ashrama. This period came to an end dramatically in August 1952 when a fire, which began near the property, burned thousands of acres of neighboring grassland and forest as well as most of the ashrama’s trees and buildings. One noteworthy survivor was the meditation cabin—the ashrama’s symbol. The fire and Shanti Ashrama made the front page in Bay Area newspapers.

Arthur Bryan, caretaker

During the next period, 1952 to 1975, there was no caretaker, and only occasional visitors came to Shanti Ashrama, usually members of the Society checking on the property or just visiting.

In 1975, in celebration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Vedanta Society of Northern California, as well as of Shanti Ashrama, the Society invited its members and friends to a daylong program, which included music, chanting, guided tours of the ashrama, and talks by four swamis about the ashrama. In 1980 the meditation cabin was extensively renovated and continues to serve as a beacon of spirituality of Shanti Ashrama’s early days

Swamis, 1975

OM Tree, 1975

Panoramic view, 1975

Meditation cabin

View from Dhuni Hill

Meditation cabin, recent

(Some of the selections in this history were taken from Sister Gargi’s “Early Days at Shanti Ashrama.”)

Suggestions for Further Reading

Atulananda,Swami. Atman Alone Abides: Conversations with Swami Atulananda. Madras: Sri Ramakrishna Math, 1978.

Atulananda,Swami. With the Swamis in America and India. Mayavati: Advaita Ashrama, 1988.

Burke, Marie Louise (Sister Gargi). “Early Days at Shanti Ashrama,” Prabuddha Bharata, August 1977 – June 1978.

Burke, Marie Louise (Sister Gargi). Swami Trigunatita: His Life and Work. San Francisco: Vedanta Society of Northern California, 1977.

Ritajananda, Swami. Swami Turiyananda: A Direct Disciple of Sri Ramakrishna. Madras: Sri Ramakrishna Math, 1963

Gallery