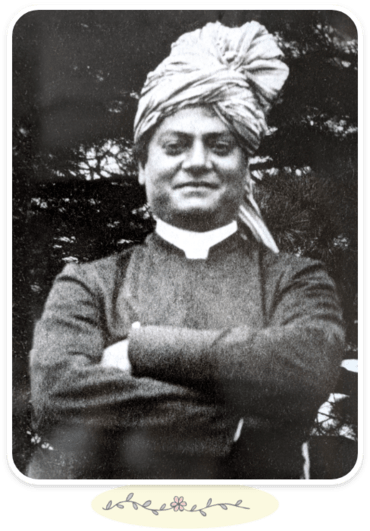

Swami Vivekananda in Camp Taylor

By the time Swami Vivekananda decided to go to the camp in Marin County under the majestic redwoods and get his “lungs full of ozone before getting into Chicago,” he had virtually finished his world mission. He had given to both India and the West “enough to last,” as he would be heard to say a little later, “for 1500 years.” Not only that—he had in California underscored, as it were, the teachings he had considered to be the most essential and had delivered them with a clarity that seemed almost cosmic in its uncompromising force.

Three tents for the women stood just below the railway embankment; Swamiji’s tent stood opposite them; beyond it, the land dropped down to the stream. To the west of his tent was the “dining area”—a wooden table and two benches—and beyond that, a cookstove and a chest for supplies. The first two days after Swamiji arrived, it rained, and he ran a high fever. Then both the weather and his health cleared, and the days settled into a rhythm of meditation, talk of God, walks along the road and through the woods, and joyous play.

The substance of that essential message was not different from the thrust of his teachings throughout his mission—“Thou art That!” His work was done. Shortly before leaving Alameda for the camp he wrote to a friend on April 18, 1900, “I am going to throw off all worry, and glory unto Mother.”

Swami Vivekananda’s state of consciousness was at this time on a level at which we can barely guess. He was no longer the teacher, per se, no longer the leader. He was the child of the Mother. It was this Vivekananda— powerful as a consummate knower of Brahman, simple as a child—who went from Alameda to Camp Irving (now a part of Samuel P. Taylor State Park) with Alice Hansbrough on May 2, 1900, to stay with other friends in a forest retreat, far from even the smallest town.

Alice Hansbrough was one of the three Mead sisters at whose house in Pasadena Swamiji had lived during a part of his eleven-week stay in southern California. At the end of February, she had come with him to San Francisco to help in all the ways his work required. Four other women were already at the camp: Lydia Bell, the leader of a San Francisco Home of Truth, to whom the camp had been lent for the summer; her young protégé Ida Ansell; Mrs. Emily Aspinall, who, with Mrs. Hansbrough, had kept house for Swamiji in San Francisco; and Mrs. Eloise Roorbach, aleader of the Alameda Home of Truth. They were all there at Miss Bell’s invitation, and all were hoping against hope that Swamiji, whom she had also invited, would come and thereby turn a pleasant vacation into never-to-be-forgotten, never-to-be-repeated days.

He would do just that. It was a clear morning when Swamiji and Mrs. Hansbrough arrived. That night “He built a fire on a spit of sand that ran out into the stream,” Alice Hansbrough recalled, “and we all sat around it in the quiet night and Swamiji sang for us and told stories.” “Now,” Swamiji said, another recalled, “imagine that you are yogis, living in the Indian forest. Forget your cities, forget everything. Think only of God.”

Swamiji would rise with the sun and, Eloise Roorbach remembered, chant by the hour. “My tent was close enough to his,” she said, “so that I could hear him chanting in the early morning. Sometimes it was very low.” Later there would be breakfast, and then, either in Miss Bell’s tent or in the redwood grove there would be talk and meditation, Swamiji lifting the minds of all into realms they had not before even dreamt of. One day after meditation in Miss Bell’s tent, Miss Bell remarked, “This world is an old schoolhouse where we come to learn our lessons.” “Who told you that?” Swamiji demanded. She could not remember. “Well, I don’t think so,” he declared.“ I think this world is a circus ring in which we are the clowns tumbling.” “Why do we tumble, Swami?” she asked. “Because we like to tumble,” was his answer. “When we get tired, we will quit.” It was a vision from the heights of Advaitic realization: he watched the joyous festival taking place, each reveler performing whatever flip or somersault he or she would, and simultaneously he saw that nothing was happening at all; there was nothing at all but Brahman. In that realm, he lived.

Sometimes the morning meditations would take place in the redwood grove, where there was no sound but that of the running stream and gently rustling trees. Then lunch, which Swamiji himself sometimes cooked.

“I close my eyes,” Ida Ansell adds, “and see him standing there in the soft blackness with sparks from the blazing log fire flying through it and a [young crescent] moon above…. He said to us, ‘You may meditate on whatever you wish, but I shall meditate on the heart of a lion. That gives strength.’… I can still feel the great peace and power of our meditation that night whenever I think of it.”

The camp lay in a wooded area through which a crystal clear stream flowed east to west. The campsite was narrow, bounded on the south and west by a little-traveled dirt road and on the north by a narrow-gauge railway, along which small wood-burning trains chugged back and forth twice daily. The camp area was not cleared of brush, as it is today; it was a flowering woodland, open enough for comfort, wild enough for a forest ashram hidden from the world. At its far end stood a small grove of towering redwoods where the campers could meditate as in a cathedral; beyond this, the woods thickened, forming a secluding wall.

“He made curry for us,” Ida Ansell recalled, “and showed us how they grind spices in India…. The meals were jolly and informal, with no end of jokes and stories.” In the afternoons, Swamiji and some of the women would go on walks through the woods. “We didn’t talk much on the walks; we just quietly went along here and there…. He was very quiet. He wanted to be quiet.”

In the evenings after dinner, they would sit around a blazing campfire. “The grand climax of the day’s activities was the evening fireside talk and the following meditation,” one of the campers recalled. “The wonderful things he talked to us in the evenings!” another exclaimed. And thus, the day would come to a close. Swami Vivekananda spent a little more than two weeks in this forest retreat, as carefree as a luminous child, making chapattis, communing with God, lifting his fellow campers without effort into his own realm of light. During those weeks, the very air became charged with spirituality, Mrs. Hansbrough would later say, more so than she had ever before known in his presence—and she had known a great deal.